RIYADH: Global food insecurity is far worse than previously thought, according to the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024 report released this week by a coalition of UN agencies, which found that efforts to combat malnutrition have suffered severe setbacks.

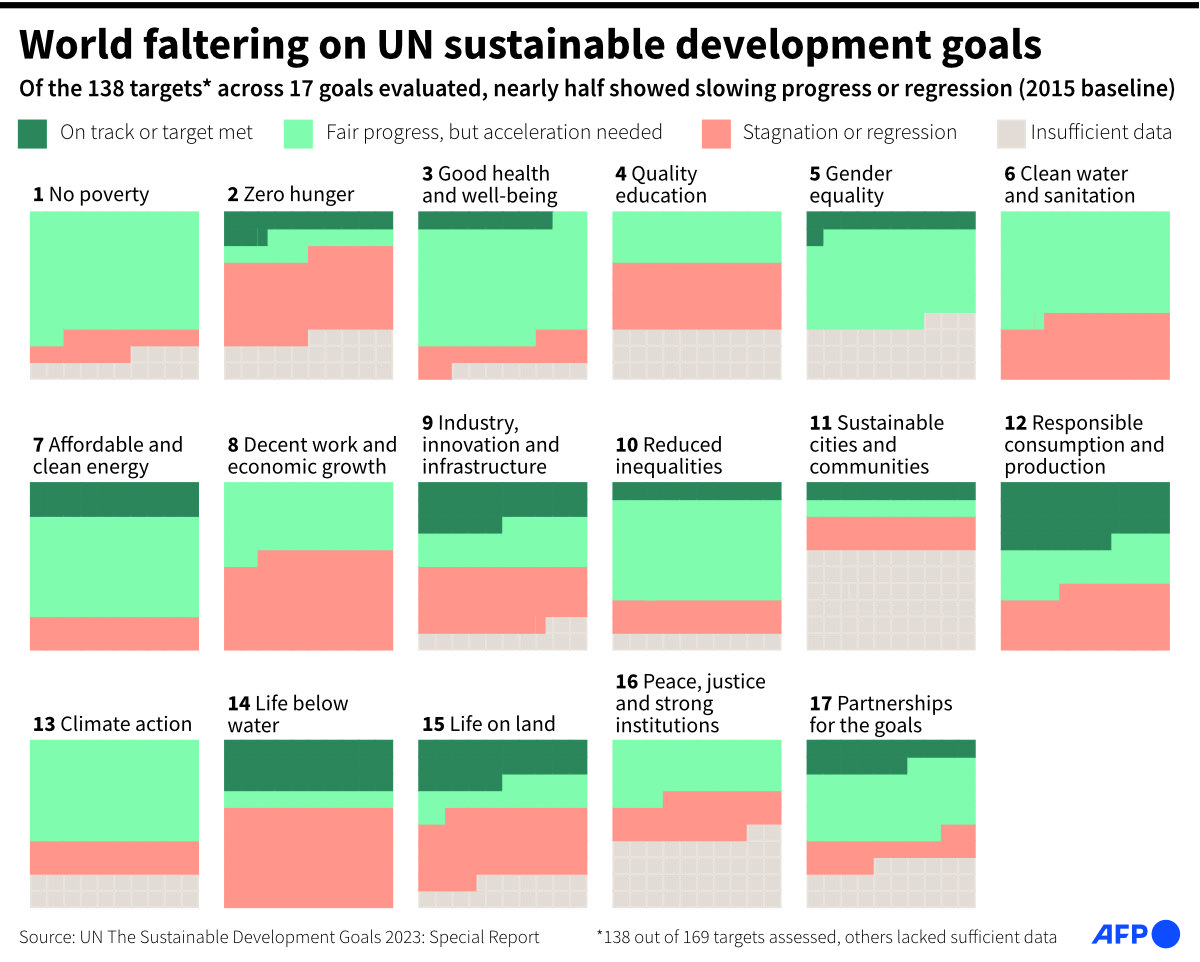

While countries around the world are far from achieving the UN's second Sustainable Development Goal of zero hunger by 2030, climate change is increasingly recognized as a key factor in exacerbating hunger and food insecurity, according to the report.

As a major food importer, the Middle East and North Africa region is considered particularly vulnerable to climate-related crop failures in the countries of origin and the resulting introduction of protectionist tariffs and fluctuations in raw material prices.

“Climate change is a factor driving food shortages in the Middle East, with both global and local shocks playing a role,” David Laborde, director of the Agricultural and Food Economics and Policy Division at the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, told Arab News.

“I think the global perspective is particularly important for the Middle East because the Middle East imports a lot of food. Even if there is no (climate) shock in your own country, if there is no drought or flood in your own country – if it happens in Pakistan, India or Canada – the Middle East will feel it.”

This section contains relevant reference points, placed in the (opinion field)

The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report has been produced annually since 1999 by the FAO, the International Fund for Agricultural Development, the United Nations Children's Fund, the World Food Programme and the World Health Organization to monitor global progress towards ending hunger.

Speaking at a recent event at UN headquarters in New York, the report's authors stressed the urgent need for creative and equitable solutions to address financial gaps in supporting countries suffering from severe hunger and malnutrition, which are exacerbated by climate change.

The report concludes that in addition to climate change, factors such as conflict and economic downturns are becoming increasingly frequent and severe, affecting the affordability of healthy food, unhealthy food environments and inequality.

In fact, food insecurity and malnutrition are worsening due to persistent food price inflation, which is undermining economic progress worldwide.

“There is also an indirect effect that we should not neglect – the interaction between climate shock and conflict,” said Laborde.

In North Africa, for example, negative climate shocks can lead to more conflict, “either because people start competing for natural resources or access to water, or simply because there are people in your area who have nothing else to do,” he said.

“There is no work, they cannot work on their farms and so they can join insurgents or other elements.”

DO YOU HAVEKNOWLEDGE?

Up to 757 million people will suffer from hunger in 2023 – that’s one in eleven people worldwide and one in five in Africa.

Despite progress in Latin America, global food insecurity has remained unchanged for three consecutive years.

There has been some improvement in the global prevalence of stunting and wasting among children under five.

At the end of 2021, the G20 countries committed to distributing $100 billion worth of unused special drawing rights held by the central banks of high-income countries to middle- and low-income countries.

Since then, however, that pledged amount has fallen by $13 billion, and the countries with the worst economic situations have received less than one percent of that support.

Saudi Arabia is one of the countries, along with Australia, Canada, China, France and Japan, that has already exceeded its 20 percent commitment, while other countries have not reached the 10 percent target or have stopped their commitment altogether.

“Saudi Arabia is a very large state in the Middle East, so what the country does is important. But it also has a financial strength that many other countries lack,” said Laborde.

“It can be done through their special drawing rights. It can also be done through their sovereign wealth fund, because where and how you invest is important to make the world more sustainable. So I say yes, it can be important to prioritise investments in low- and middle-income countries in food and security programmes and nutrition-related programmes.

Although malnutrition in Saudi Arabia has declined in recent years, the report shows that stunting among children has actually increased by 1.4 percent over the past decade.

As the population has grown, so has the number of overweight children, obesity and anemia in women. In this sense, it is not so much a lack of food, but a lack of healthy eating habits.

“Saudi Arabia is a good example of how traditional hunger and food shortages are, in my opinion, becoming less of a problem, but other forms of malnutrition are coming to the fore,” said Laborde.

In 2023, approximately 2.33 billion people worldwide were moderately or severely food insecure and one in 11 people suffered from hunger, exacerbated by various factors such as economic decline and climate change.

The affordability of healthy diets is also a critical issue, particularly in low-income countries where over 71 percent of the population cannot afford adequate nutrition.

In countries like Saudi Arabia, where overnutrition is a growing problem, adequate investment in nutrition and health education and policy adjustments may be the way forward, says Laborde.

While the Kingdom continues to provide aid to crisis-hit countries such as Palestine, Sudan and Yemen through its humanitarian arm KSrelief, these states continue to struggle with dire conditions. Gaza in particular has suffered the consequences of the war with Israel.

“Even before the conflict began, especially at the end of last year, the situation in Palestine was complicated, both in terms of the agricultural system and population density. There was already a problem of malnutrition,” said Laborde.

“It's the same everywhere, in Sudan, Yemen, Palestine: when conflicts and military operations are added to the mix, the population suffers greatly because production is destroyed. Access to water is destroyed. But people also can't go shopping if the truck or ship that brings the food isn't working.”

Although Palestine and Sudan are the extreme cases, around 733 million people worldwide still suffer from hunger. This means that the high level of the past three years remains unchanged.

“On the ground, we are working with the World Food Programme and other organisations to bring food to the needy people in Palestine,” said Laborde of the FAO's work. “Before and after the conflict, we will also work to rebuild things that need to be rebuilt. But without peace, our options are limited.”

FAO helps food-insecure countries by providing better seeds, animals, technology and irrigation solutions to develop production systems. At the same time, it works to protect livestock from pests and diseases by providing veterinary services and creating incentives for countries to adopt better strategies.

The report's projections for 2030 suggest that around 582 million people will still suffer from chronic malnutrition, half of them in Africa. This is in line with the level seen in 2015, when the SDGs were adopted, and suggests a plateau.

The report stresses the need to create better systems of financial distribution in line with this year's theme: “Financing to end hunger, food insecurity and all forms of malnutrition.”

“In 2022, there were many headlines about global hunger, but today the issue has more or less disappeared, even though neither the number of hungry nor the number of starving people has decreased,” said Laborde, pointing to the negative impact of the war in Ukraine on global food prices.

“We have to say that we are not keeping the promises of politicians. The world produces enough food today, so it is much more about how we distribute it, how we provide access. It is a man-made problem, so it should also be a man-made solution.”